There is a quiet inevitability in the universe, one that hums beneath the surface of all existence. The stars burn, galaxies swirl, and life continues to unfold—but in the distance, in the dark spaces between these actions, a question lingers, growing more insistent with each passing moment: What happens when it all stops? Not just the stars or the planets, but time itself. The heat death of the universe is an idea that pulls at the edges of understanding, a glimpse into a future where everything—the very essence of existence—fades into a cold and lifeless expanse. I have often wondered if we, too, are heading toward this final fate, where nothing will ever change again. But before we can understand where we are going, we must first explore how we got here and why this ultimate end is so undeniably certain.

It was in the late 19th century that the first inklings of this cosmic doom began to take shape. Scientists, delving into the mysteries of thermodynamics, started to realize that the universe was not a perpetual motion machine. Instead, it was bound by laws—specifically, the second law of thermodynamics, which tells us that all systems, over time, will move toward a state of greater disorder. Entropy, the measure of this disorder, will always increase until it reaches a point where no more work can be done. The universe, once a dynamic entity of stars and galaxies, will one day reach a state where energy is uniformly distributed, and nothing will ever change again. This state, where all activity ceases, is what we refer to as the heat death of the universe.

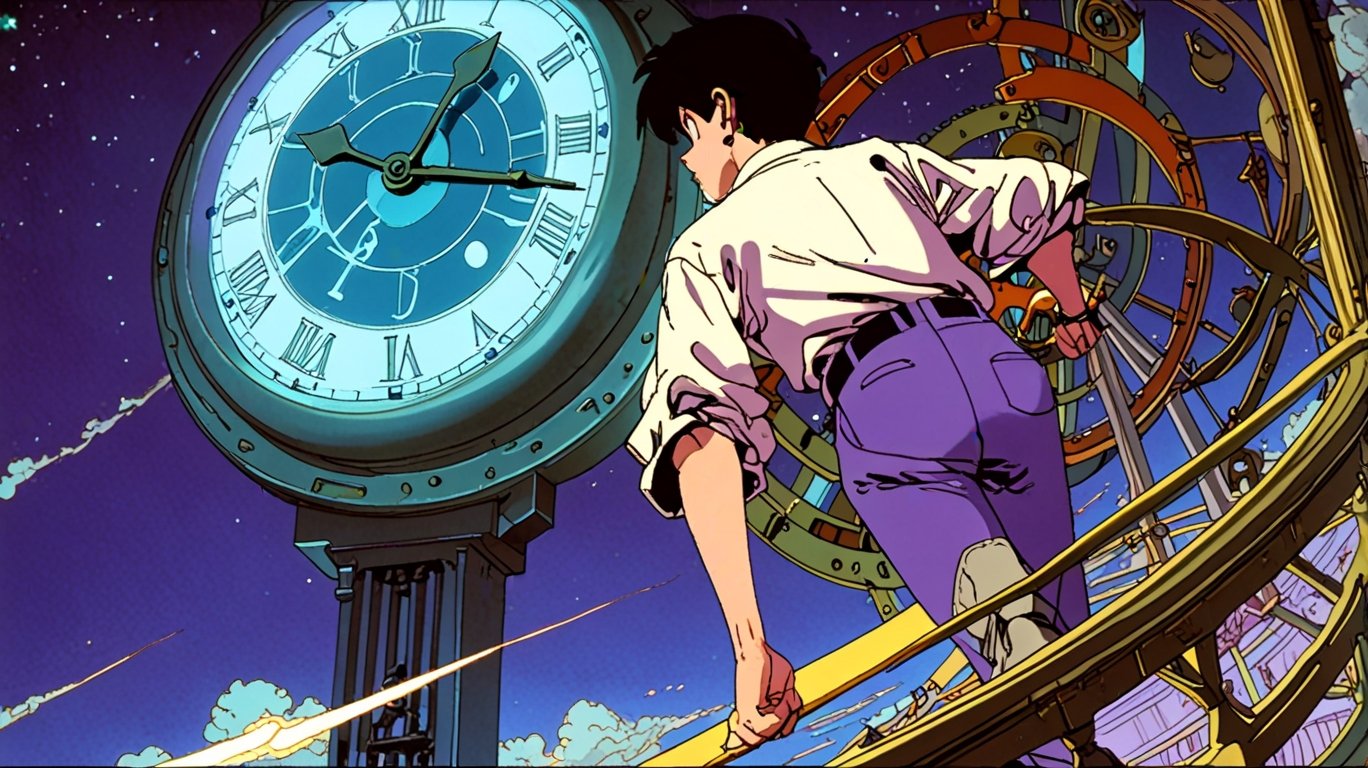

But this is not merely a theoretical event far in the future—it is the very nature of time. Time itself, as we experience it, is defined by change, by the flow of energy and the interactions between particles. Without energy, there is no change, and without change, time loses its meaning. We begin to realize that the heat death of the universe is not just the end of stars; it is the end of time itself. The slow decay of energy, the slow dissipation of all motion, will lead to a universe frozen in eternity, where nothing ever happens again.

I find myself captivated by this concept, and yet, there is something profoundly unsettling about it. How does one come to terms with the idea of an eternal silence, where no life exists, no stars shine, and no memory remains of the vibrant universe that once was? The more I think about it, the more I feel drawn to explore the implications of this inevitability, to understand what it means for us, for life, and for the very fabric of existence. What happens when the heat death of the universe arrives? Will we even be here to witness it?

The truth, as it often is, is far more complex than we might imagine. While the second law of thermodynamics assures us that entropy will increase, it is not a simple, linear process. The universe is a complex system, with interactions and forces that we are only beginning to understand. One of the most fascinating phenomena in this context is the idea of black holes. These mysterious objects, once thought to be purely destructive, might actually hold the key to understanding the universe’s ultimate fate. Some theorists suggest that black holes, through a process called Hawking radiation, might slowly lose their mass and energy, eventually evaporating entirely. If this is true, black holes will not be the final remnants of the universe, but rather a temporary feature in a much longer, much more intricate process leading to heat death.

But how does this relate to us, to life on Earth, and to our place in the vast cosmos? It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the heat death of the universe is a distant, impersonal event, something that will occur long after we are gone. But that is not the case. The heat death is already happening, in a sense. It is the quiet background hum of cosmic change that we often overlook, an undercurrent that shapes the destiny of every star, every galaxy, and every atom. It is a reminder that nothing, not even the most brilliant stars, can escape the inexorable pull of entropy.

Yet, I can’t help but wonder if there is still hope, some way to delay or even prevent the heat death of the universe. Could we, as a species, find a way to tap into the forces that govern the cosmos? Could we use the knowledge we have gathered to slow down or even reverse the effects of entropy? Some scientists have suggested that the key might lie in understanding and harnessing dark energy—the mysterious force that is causing the universe to expand at an ever-increasing rate. If we could tap into this energy, might we be able to stretch out the universe’s timeline, or even create new forms of life and energy that defy the laws of thermodynamics?

I find these ideas both thrilling and terrifying. The more I explore the possibilities, the more I am reminded of our own fragility. The heat death of the universe is not just a cosmic event; it is a reflection of the limits of existence itself. It forces us to confront the ultimate question: What is the purpose of life if it is all destined to end in silence? And yet, in that very silence, there lies a profound truth. The heat death of the universe is a reminder of how fleeting and precious each moment is, how every action, every thought, and every breath is part of a larger, infinitely complex tapestry of existence.

As I sit in contemplation, I feel the weight of this mystery pressing upon me. The heat death of the universe may be inevitable, but it is also a call to action. It challenges us to live fully, to explore the mysteries of the universe with a sense of urgency and wonder. For in the face of such an overwhelming fate, the true value of life is not in the answers we find, but in the questions we ask along the way. Perhaps that is the greatest mystery of all—that even in the shadow of the inevitable, we continue to seek, to discover, and to understand.

The heat death of the universe may be an end, but it is also the beginning of something deeper—a reminder of the fragility and wonder of existence, and a challenge to make the most of the time we have, however fleeting it may be.